Over $30 million down the drain — how it happened

Through the 1940s and ’50s, it held more than 60% of the market. Pepsi had been around but they'd floundered, going bankrupt several times while attempting to sink their teeth into the market.

However, by the 1970s, Pepsi had found its stride after several hit marketing campaigns. Where Coke’s primary demographic was older adults, Pepsi was winning over an expanding, younger demographic.

By 1980, Pepsi was only trailing coke by 3%.

This, unsurprisingly, made Coke very uncomfortable. They then did what one should never do when under pressure: overreact.

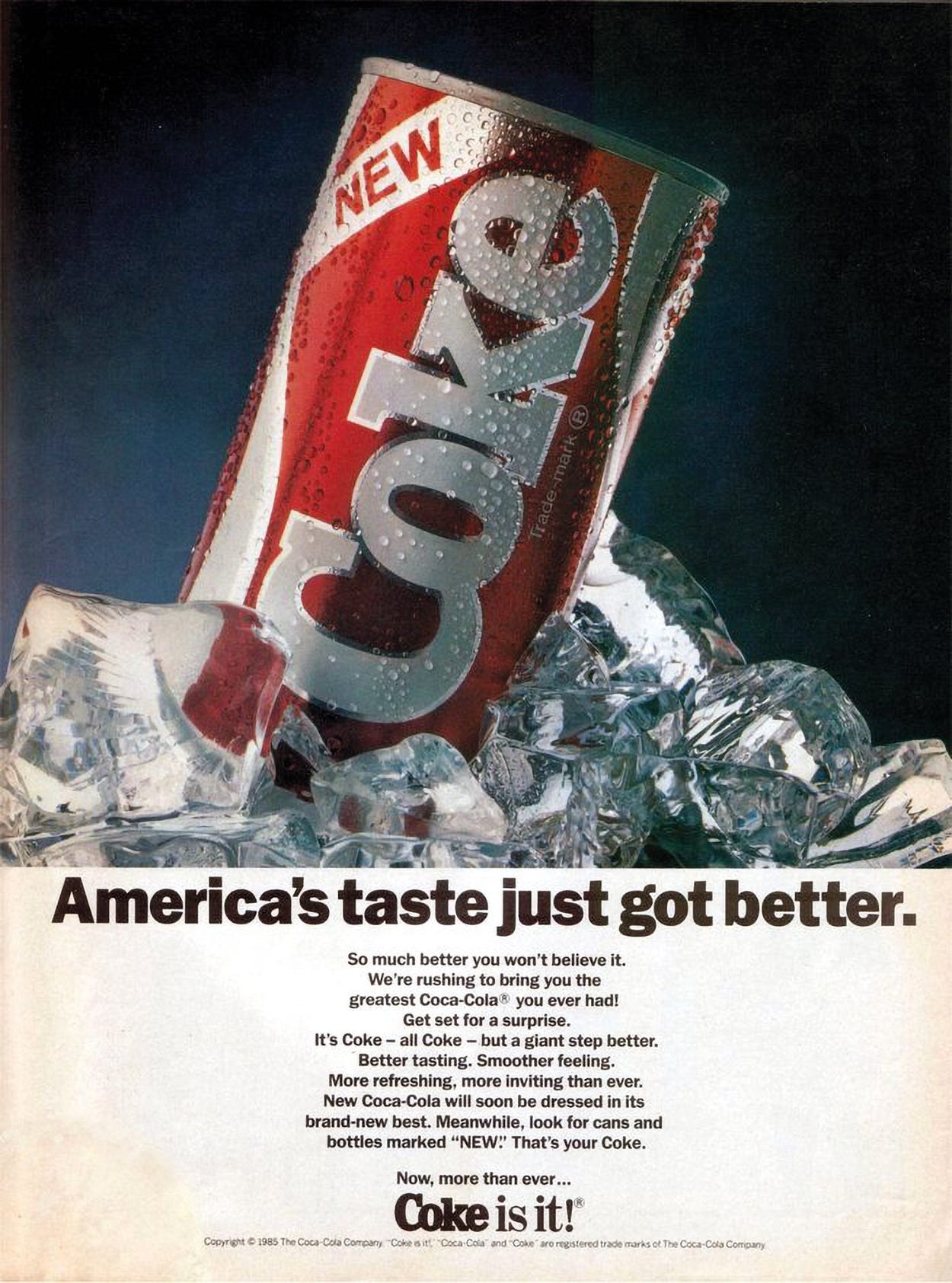

They changed the original recipe.

But they hadn’t made this decision without favorable data. So what went wrong?

The Crack in the Process

Months earlier, Coca-Cola had begun “Project Kansas.” It sounds like a nuclear experiment but it was just a testing project for the new flavor.

In individual surveys, they’d found that more than 75% of respondents loved the taste, 15% were indifferent, and 10% had a strong aversion to the taste to the point that they were angry.

When researchers did surveys in group settings, they noticed the angry 10% exerted subtle peer pressure effects on the group.

When New Coke was released, that 10% manifested in a big way. They began getting loud about their displeasure in the new recipe. News outlets began picking up on them, amplifying their voices, causing things to snowball.

A consumer action group, Old Cola Drinkers of America, formed and began to collectively protest the new recipe (some people clearly have a lot of time on their hands).

Additionally, Coke made a big cultural mistake. Coke is headquartered in the Deep South (Atlanta).

Many patrons from the region saw the flavor change as another concession to the north, to the liberal minds that liked Pepsi.

At the time, Coca-Cola had a customer hotline. It was flooded with more than a thousand phone calls a day with people airing their grievances.

Confused at the sudden backlash, Coke executives hired a psychiatrist to listen in who later said, “Some people sounded as if they were discussing the death of a family member.”

Pepsi pounced — running their own ads making fun of Coke’s mistake. In turn, Pepsi and Coke’s market shares drew even.

Major media publications, smelling blood, pounced as well.

Invariably, Coke saw a decline in sales and, far more importantly, major damage to their golden brand perception.

The Bizarre Switch

It’s interesting that so much of the data had been favorable beforehand.

Where surveys had shown more than 70% preference for New Coke, surveys afterward showed less than 13%.

Where professional critics had said good things in prior surveys, they now became more negative, with Mimi Sheraton saying, “New Coke seems to retain the essential character of the original version…It tastes a little like classic Coca-Cola that has been diluted by melting ice.”

The trend factor proved to be massive in the perception of the new flavor. It got to the point where fans booed Coke commercials in sports arenas.

Just three months after the release of New Coke, the president of Coca-Cola aired a commercial announcing that coke would return and took the unprecedented step of announcing they’d made a mistake.

And hence, today, you will notice that all Coca-Cola either says “classic” on the can or “original” on the container holding the cans.

Coke lost $30M in the unsold New Coke inventory and the $4M on research it spent. This is approximately $82 million in 2020 dollars.

Today, the story of New Coke is a poster child for marketing disasters. It is taught in nearly every marketing program in the United States.

So where is the nuance in all this? Why did Coke catch so much crap just for changing a recipe? Three reasons:

- They ignored the unrelenting power of peer pressure. Many users in public found themselves avoiding New Coke for fear of judgment.

- They learned the importance of honoring your biggest brand advocates. The heaviest consumers of your products will have exponentially louder voices. This is why filmmakers tasked with doing remakes and sequels have such a treacherous job.

- They forgot the cultural value of Coke. Coke has a long history and brings feelings of nostalgia to its drinkers.

Not all products are like cars and electronics. They can’t just be tweaked and changed like a new version of an iPhone.

With the New Coke disaster, it seems there has never been a more applicable use of the phrase, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

Comments

Post a Comment